Wayne McGregor, il nuovo direttore britannico cinquantenne della Biennale Danza di Venezia, ha voluto restaurare, a Dartington nel Sud-Est dell’Inghilterra, la casa-studio dove visse il coreografo tedesco Kurt Jooss, fuggitivo dal Nazismo.

Jooss, che aveva rifiutato di allontanare dalla sua compagnia il compositore Fritz Cohen e i suoi danzatori ebrei, avvisato appena in tempo del pericolo di una retata, nel 1933, passando per l’Olanda, era riuscito a raggiungere le sponde inglesi, da cittadino di un paese nemico, restando nell’isola fino al 1949, quando riprese la sua attività a Essen, nella Tanzschule frequentata da Pina Bausch, di ritorno dagli USA.

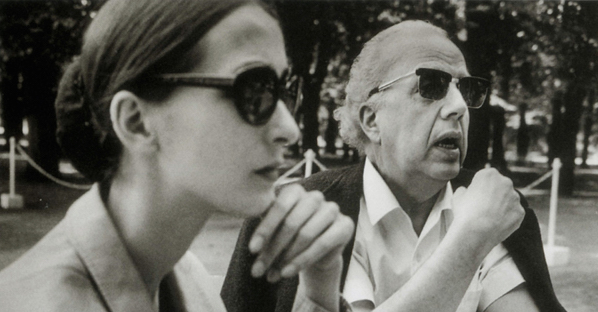

La coreografa più influente del Tanztheater tedesco del dopoguerra, aveva interpretato per Jooss il ruolo della madre dolente in Der Grüne Tisch, il lavoro del 1932 con cui Jooss mise in scena un apologo contro gli orrori della guerra.

Il tavolo verde del titolo è quello dei potenti che si giocano cinicamente il destino dei popoli, mandati a morire sui campi di battaglia.

Altri esponenti dell’Ausdruckstanz tedesca, con la sua Körperkultur, l’amore per il movimento nella natura, l’esaltazione della salute con l’esercizio, un fenomeno capillare supportato dal governo tedesco, non avevano preso le distanze dal Nazismo. Mary Wigman avrebbe dovuto portare la danza alle Olimpiadi del 1936; anche Rudolf Laban, teorico del corpo e della sua meccanica, che poi raggiunse Jooss in Inghilterra, avrebbe dovuto essere della partita.

Isa Partsch-Bergsohn nel suo libro Modern Dance in Germany and the United States: Crosscurrents and Influences, ha riportato a galla molto del “non più detto”.

Anche Susan Manning nei suoi Ecstasy and the Demon (2006) e New German Dance Studies ha fatto luce sul passato rimosso.

Nel 1939 Olympia di Leni Riefenstahl, ex danzatrice e regista prediletta di Hitler, aveva lanciato uno sguardo interno alla cultura del corpo di quell’epoca.

Nel dopoguerra la Germania Ovest preferì tagliare con la sua danza “espressiva” coinvolta nel regime sconfitto, e favorire il balletto classico, a Stoccarda- direttore John Cranko, sudafricano di matrice inglese, ad Amburgo – direttore l’americano John Neumeier – e a Monaco, sotto la guida dell’alsaziano Marcel Luitpart e poi del russo Victor Gsovsky; la Germania Est subì l’influenza russa.

Berlino, dopo la guerra, aveva tre compagnie di balletto, quella della Komische Oper a Est, quella della Staatsoper a Ovest, e quella della Deusche Oper, confluite nel Staatsballett Berlin dal 2004 dopo l’unificazione e anche a causa della crisi economica.

Solo negli anni Settanta del 900 il Tanztheater si riaffacciò sulle scene tedesche e internazionali, soprattutto con le tre coreografe, Pina Bausch, Susanne Linke e Reinhild Hoffmann, che riannodarono i fili di una storia perduta.

Leggi dello stesso autore:

Geodance, Ninette de Valois and Germaine Acogny

Modern geodance in Europe

Wayne McGregor, the new fifty-year-old British director of the Venice Biennale Danza, wanted to restore, in Dartington in the South-East of England, the house-studio where the German choreographer Kurt Jooss, a fugitive from Nazism, lived.

Jooss, who had refused to remove composer Fritz Cohen and his Jewish dancers from his company, warned just in time of the danger of a raid, in 1933, passing through Holland, had managed to reach the English shores, as a citizen of an enemy country, remaining on the island until 1949, when he resumed his activity in Essen, in the Tanzschule frequented by Pina Bausch, on his return from the USA.

The most influential choreographer of the post-war German Tanztheater, she had played for Jooss the role of the grieving mother in Der Grüne Tisch, the 1932 work with which Jooss staged an apologue against the horrors of war.The green table of the title is that of the powerful who cynically play the fate of peoples, sent to die on the battlefields.

Other exponents of the German Ausdruckstanz, with its Körperkultur, the love for movement in nature, the exaltation of health with exercise, a widespread phenomenon supported by the German government, had not distanced themselves from Nazism. Mary Wigman was supposed to take dance to the 1936 Olympics; Rudolf Laban, a theorist of the body and its mechanics, who later joined Jooss in England, should also have been in the game.

Isa Partsch-Bergsohn in her book Modern Dance in Germany and the United States: Crosscurrents and Influences, brought up much of the “no longer said”.

Susan Manning in her Ecstasy and the Demon (2006) and New German Dance Studies also shed light on the repressed past.In 1939, Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, Hitler’s favorite former dancer and director, had cast an inside look at the body culture of that time.

After the war, West Germany preferred to cut with its “expressive” dance involved in the defeated regime, and favor classical ballet, in Stuttgart – director John Cranko, South African of English origin, in Hamburg – director the American John Neumeier – and in Munich, under the leadership of the Alsatian Marcel Luitpart and then of the Russian Victor Gsovsky; East Germany came under Russian influence.

Berlin, after the war, had three ballet companies, that of the Komische Oper in the East, that of the Staatsoper in the West, and that of the Deusche Oper, which merged into the Staatsballett Berlin since 2004 after unification and also due to the economic crisis.

Only in the 1970s did the Tanztheater reappear on the German and international scenes, especially with the three choreographers, Pina Bausch, Susanne Linke and Reinhild Hoffmann, who re-tied the threads of a lost history.

You can also read: