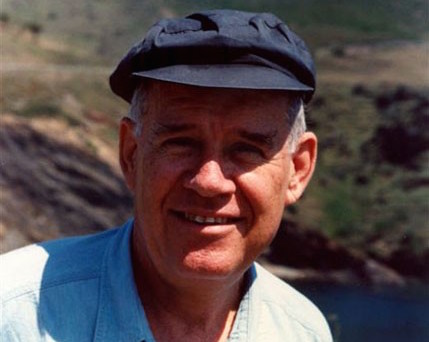

One of the greatest artists of the second half the twentieth century has passed away at the age of 90. Mourning not only in the world of art and culture in general. In fact, no less, Karavan leaves an unbridgeable void in the very fragile field of human rights and peace (many of his relatives killed during the Second World War and the Nazi holocaust). Those subjects inspired many of his main works all over the world, starting with his Tel Aviv where he was born in 1930 and where he died on the 29th. last May. That’s why the mayor of the city said “son of the city and honorary citizen of the city”. After having studied Drawing and Painting at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem, in 1956 he thought of Europe and went to Florence to study Painting. In the same Italian city, exactly at the Forte Belvedere, in 1978 he will create a memorable huge environmental installation using laser beam. Our friendship started in the second half of the Seventies, with many meetings in Paris (also, in recent years, he has given his high cultural and ethical contribution as a member of FYINpaper’s Scientific Committee).

Thanks to Karavan, sculptural art takes the path of the environment with great strides and at a high level. That’s why in my book on Environmental Art (1983) the Israeli artist became a decisive and essential reference. In that publication for the first time, the theoretical foundations of that trend were fixed, far beyond the even interesting actions in nature ruled by artists of various nations.

With this “new” expressive dimension, and with Dani Karavan (but not only with him of course, although no one was like him), art emphasized its important Renaissance-like role in society. In fact, it directly concerns social life, it is useful, you step on it, you live in it, it is a real and not a hypothetical environmental fact. In addition, in the case of Karavan, it assumes a strong ethical connotation especially in relation to the themes of peace and human rights.

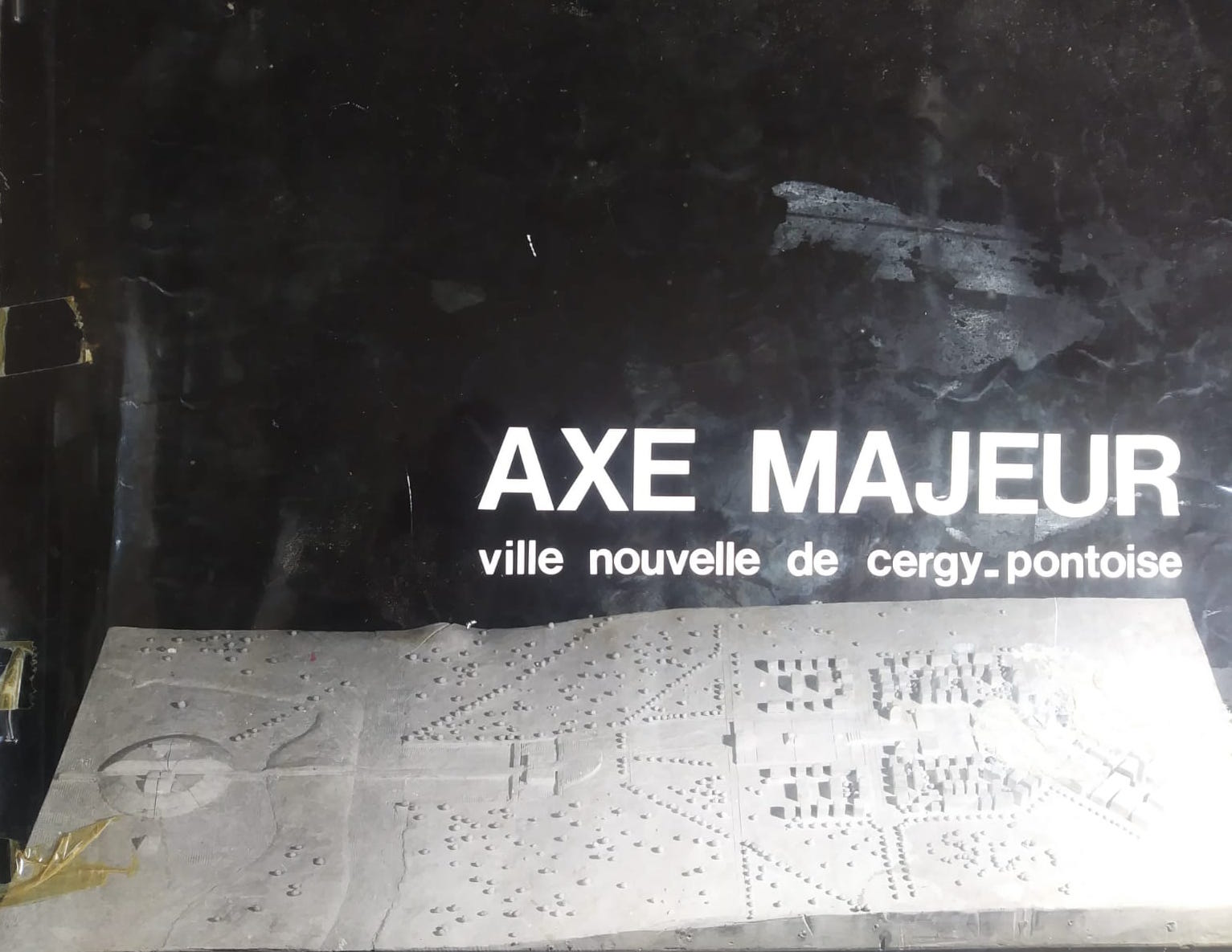

In this sense Dani’s works are numerous, and above all of great creative and expressive value, in many countries. It is worth underlining how often these projects take on an urban extension. We limit citing the great design commitment poured into Paris where Karavan went further with his training and where he lived for several decades. I am referring to the large Axe Majeur project he designed for the grouping of municipalities that goes by the name of Cergy Pontoise, a suburb of Paris in the north-east direction. In 1980, President François Mitterrand took up an idea of his predecessor Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. The Spanish architect Ricardo Bofil contributed to the project.

But it is an absolutely Karavanian work even in its symbolic values (for example, 12 columns, 12 stations), various walkways, overlooking the Défense and the Arc de Triomphe, a column 36 meters high and wide 3.60. A work of monumental commitment but totally distant from the sense of the monument and which is spread over three kilometers.

Dani Karavan passed away

Uno dei grandi artisti della seconda parte del Novecento se ne è andato, a 90 anni. Compianto non solo nel mondo dell’arte e della cultura in generale. Infatti, non meno, Karavan lascia un vuoto incolmabile nel terreno delicatissimo dei diritti umani e della pace (molti suoi parenti uccisi durante la guerra e l’olocausto nazista). Temi, questi, ai quali ha dedicato diverse delle sue opere capitali ovunque nel mondo, a cominciare dalla sua Tel Aviv dove era nato nel 1930 e dove è morto il 29 maggio scorso e il cui sindaco lo ha dichiarato “figlio della città e cittadino onorario della città”.

Dopo avere frequentato Disegno e Pittura alla Bezalel Academy of Art and Design a Gerusalemme, nel 1956 guarda all’Europa e va a Firenze a studiare pittura dove, nel 1978, realizzerà, precisamente al Forte Belvedere, una memorabile installazione di largo respiro ambientale con uso del raggio laser. La nostra amicizia risale alla seconda parte degli anni Settanta, con tanti incontri a Parigi (in anni recenti, ha peraltro dato il suo alto contributo culturale e etico al Comitato Scientifico di FYINpaper).

Con Karavan, l’arte scultorea prende a grandi passi e ad alto livello, la via dell’ambiente. Non a caso nel mio libro sull’Arte Ambientale (1983) nel quale, per la prima volta si davano i fondamenti teorici di quella tendenza (ben al di là dei pur interessanti interventi nella natura da parte di artisti di varie nazioni), l’artista israeliano diventava riferimento determinante e imprescindibile. Con questa “nuova” dimensione operativa, e con Dani Karavan (ma non solo lui ovviamente, anche se nessuno come lui), l’arte assumeva un ruolo importante nella società, un po’ alla maniera rinascimentale.

Infatti, essa riguarda direttamente il vivere sociale, è utile, la calpesti, ci vivi dentro, è fatto ambientale reale e non ipotetico. In aggiunta, nel caso di Karavan, essa assume una connotazione etica forte specie in rapporto ai temi della pace e dei diritti umani. E in queste senso le opere di Dani sono numerose, e soprattutto di grande respiro ideativo ed espressivo, realizzate in tante parti del mondo. Importante sottolineare come spesso questi suoi progetti assumano un’estensione urbanistica.

Basterà citare il grande impegno progettuale riversato a Parigi, dove peraltro ha perfezionato la sua formazione, e dove è vissuto per parecchi decenni. Mi riferisco al grande progetto Axe Majeur studiato per il raggruppamento di comuni che va sotto il nome di Cergy Pontoise, banlieue di Parigi in direzione nord-est. Nel 1980 il presidente François Mitterrand riprende un’idea del predecessore Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. Contribuisce al progetto Ricardo Bofil.

Ma si tratta di opera eminentemente karavaniana, che si sviluppa lungo tre chilometri, persino nei valori simbolici (ad esempio, 12 colonne, 12 stazioni), vari camminamenti, affaccio sulla Défense e sull’Arco di Trionfo, una colonna alta 36 metri e larga 3,60. Opera di impegno monumentale ma lontana totalmente dal senso del monumento.

Pierre Restany, grande amico e sodale di Karavan, nel 1981 così scriveva nella prefazione al dossier nel quale veniva sintetizzato il progetto: “Un’impresa originale, nuova, audace nella misura in cui è profondamente umana (…) che si inscrive nella linea storica della tradizione urbanistica della regione parigina e che punta a integrare il fatto costruttivo alla natura degli uomini e delle cose”.

Umano, amante della solidarietà, anche se schivo, intransigente nel suo lavoro, dotato di straordinaria inventiva progettuale, poesia, senso della misura anche nelle opere di grandi proporzioni. I suoi meriti sono stati ampiamente riconosciuti: Premio Imperiale del Giappone (equivalente del Nobel in arte), primo artista Unesco per la pace, Cavaliere di Francia “Légion d’Honneur”. Tuttavia Karavan verrà sempre più studiato e ammirato, fino alla popolarità, quasi uomo fuori dal tempo per i suoi alti valori creativi e di pensiero sociale interculturale.

Da chi scrive e da tutto lo staff di FYINpaper il nostro commosso ricordo e gratitudine, e un abbraccio amichevole alla moglie Hava, ai figli e ai nipoti.