The memory was nourished with them, filled with a fragile sadness, even on my words. Leonardo and Stefano told of substantial moments lived in Caltanissetta, of goliardia (goliardey spirit), of trifles; also of how Sciascia, as a young student, possessed a long, too long raincoat, probably waiting, as it was used in those lean times, for subsequent body growth. And then of his teacher aunts who had so much influence on his domestic adolescent life. And also of Lilly Bennardo and Alfonso Campanile, of their teachers, of the confidentiality of Brancati, of Giugiù Granata and of the sacred figure of Calogero Bonavia, the author of Servi, of the culture of Luca Pignato, of Luigi Monaco, of the films seen and welcomed into the passionate curiosity of their hearts. The absorbed tension stretched across Sciascia’s face is the same that I would find, intact, a few years later, in a host of drawings by the lonely Palermitan painter Ermanno Gagliardo that I cured in the space of the Galleria Flaccovio. In that sheet Leonardo’s face appears stubbornly centered on himself, on his thought, when he spreads his gaze and mimicry through a concise citation of those ‘carusi’ (road children) plagued by mines and portraits, in a very distant 1905, by Onofrio Tomaselli, artist from Bagheria lovingly appreciated by Renato Guttuso. The education of Sciascia, sixteen years old, already appears solid in that school year 1936-’37, while attending the Magistral Institute, the year in which Vilardo, by ‘virtue’ of a failure, becomes his classmate, and with him, “uncommon intellect”, their indivisibility confirms itself in a Caltanissetta “restful, sometimes insipid, a boring town as Brancati insinuated; but for us, born, lived and raised in humble agricultural villages, [Stefano in Delia, Leonardo in Racalmuto], it was a sweet, active and vital center ». A pupil, Vilardo insists in his A scuola con Leonardo Sciascia, «good, generous, altruistic, man of very few words, a value that our politicians lack today. He helped his companions who had some difficulties in developing themes: to those who gave the start, to those who lent a hand if they had run aground and could not continue on their way, to those who dictated a brilliant closing … reserved, cultured, and characterized by a disarming modesty. Just with Stefano Vilardo, Sciascia shares all the vital experiences from Caltanisetta to Palermo. A friendship lived as an urgency of existential ‘verification’, of which he had mentioned in an interview with the journalist Davide Lajolo: it seemed necessary, at a certain point of their emotional journey, to take further stock, to make comparisons, to evaluate the congruity actions, reassured passions, friendships, and constantly bring out, in a hand-held way, the constitutive fullness of loyalty accepted as a salvific relief.

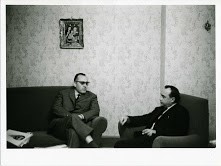

Sciascia repeated all this in 1981, with convinced clarity, in Conversazione in una stanza chiusa with Lajolo, in which he reminds the interlocutor:

“How I was and how I am I check with an old school friend of mine: together since 1935, in Caltanissetta, in Palermo, we sometimes find ourselves, especially when we meet other old classmates, that the two of us are not in nothing changed. He was catholic and christian-democrat (but in recent years no longer christian-democrat), I was a christian without Church and a socialist without party. For forty-five years we lived without even the slightest discrepancy, recognizing or finding ourselves in the most-risky good faith, honesty, courage. But you ask me about the elementary school teacher. Well, I would say that I still am: I cannot describe writing except as a good deed”.

But, as you know, Sciascia will show its own revolution experienced in Caltanissetta, by collaborating with the publishing house of the bookseller Salvatore Sciascia, maturing the lively and balanced direction of “Galleria” and intellectually supporting the care of the white “Quaderni di Galleria”. In them he establishes ties with well-known writers, poets and artists; makes cultural and human choices out of the ranks by showing more and more his acute sensitivity towards words, and towards writing as a consequence of seeing, and the fallout of this seeing on the social and civil society lighting the fire of indignation and reflection on the future and memory. In this way, his essays Pirandello e il pirandellismo e Pirandello e la Sicilia, the anthology Il fiore della poesia romanesca presented by Pier Paolo Pasolini have pre-eminently their germination in Caltanissetta (32 years of life in this city before moving to Palermo in 1967) and, in parallel, other exercises aimed at the gnomic value of the word such as Favole della dittatura then illustrated by ten drawings by Giosetta Fioroni and published, -so for the poetic collection La Sicilia, il suo cuore strengthened by the bends of Emilio Greco, – by the Roman Bardi, until he published, a little further on time, Parrocchie di Regalpetra and Morte dell’inquisitore, which mark his debut at Laterza publisher.

The work of those years was affected, not secondarily, by talks and attentions to the intelligence of the area, to voices placed in the background, and where lived examples such as Luca Pignato or the principal Luigi Monaco, to which the writer of Racalmuto looks with deep admiration. Just this year, (creative and critical) unpublished works were collected by Antonio Vitellaro as part of the thirtieth anniversary of Sciascia’s death, also embarking on a moving journey around his life and opening a way to clarify what is unjustified as cruel shadows that greatly disturbed the intellectual. An intellect which appears to be comforted by Leonardo’s honest declaration when he says he could not forget the “evenings spent in a corner of Salvatore Sciascia’s bookstore, conversing with Luigi Monaco”, and how those unforgettable evenings had been in some ways “his university”. In that tiny universitas a handful of intellectuals, artists and poets, led by Leonardo, comfort with their intellect “Galleria“, a bimonthly review.

Essential Bibliography

Sergio Mangiavillano, I piaceri dell’umorismo. Vitaliano Brancati a Caltanissetta (1937-1938), Salvatore Sciascia Editore, Caltanissetta-Roma 2004; Stefano Vilardo, Tutti dicono Germania Germania, (Nota di Leonardo Sciascia e postfaz. di Aldo Gerbino), Sellerio, Palermo 2007; Stefano Vilardo, A scuola con Leonardo Sciascia, Sellerio, Palermo 2012; Aldo Gerbino, Cammei, Pungitopo, Marina di Patti 2015; Leonardo Sciascia, Nessuno è felice: tranne i prosperosi imbecilli, (“Lettere a Stefano Vilardo-1940-1957”; postfaz. di Beppe Benvenuto e Giancarlo Macaluso), De Piante Editore, Milano 2018; Antonio Vitellaro, Il Preside Luigi Monaco (1892-1958) e il recupero dei suoi scritti inediti, Società Nissena di Storia Patria, Caltanissetta 2019.