Pubblicato su Fyinpaper il 25 febbraio 2021

Published in Fyinpaper on 25 February 2021

It is a pleasure to lend an ear to two megaphones of the caliber of the two artists cited to get at that colossus (of Rhodes?) that bears the name of Marcel Duchamp. It’s been exactly 34 (1) years since I started my battle, but my bullets bounced off a rubber wall rebounding to the sender. I have to thank heaven if I have come out unscathed so far. The thread of the discourse of the two unravels very clearly in different fields that never touch visual art, but it is also valid for this. Substantiated by very few others (including Susan Sontag and Franco Vaccari), it cannot be dismissed as biased: which, if one speaks of music and the other of poetry?

So let’s keep in mind what JB and GG say about their fields, but let’s ask ourselves why there should be a different discourse in that of visual art. If we give the etymological meaning to semantics and not that of the expression of its content, every interpretation, as Sontag (2) states, is a usurpation, a grand deception. Art cannot exhibit any semantic content separate from its form, because it is exactly this that conveys it. The ambiguity linked to the meaning does not interest us, but the mystery of form does (3). If a plethora of exegetes have strived, with good results for their profit, to give an explanation to the convoluted arguments of the “Frenchman”, this does not justify forgetting that the visual language possesses an autonomy of signs that do not preclude the past and are in search of a future that has nothing to do with the lingua franca, even that of the most distinguished critics, one that does not suffer from a translation. Even mine right now: I don’t pretend to do poetry.

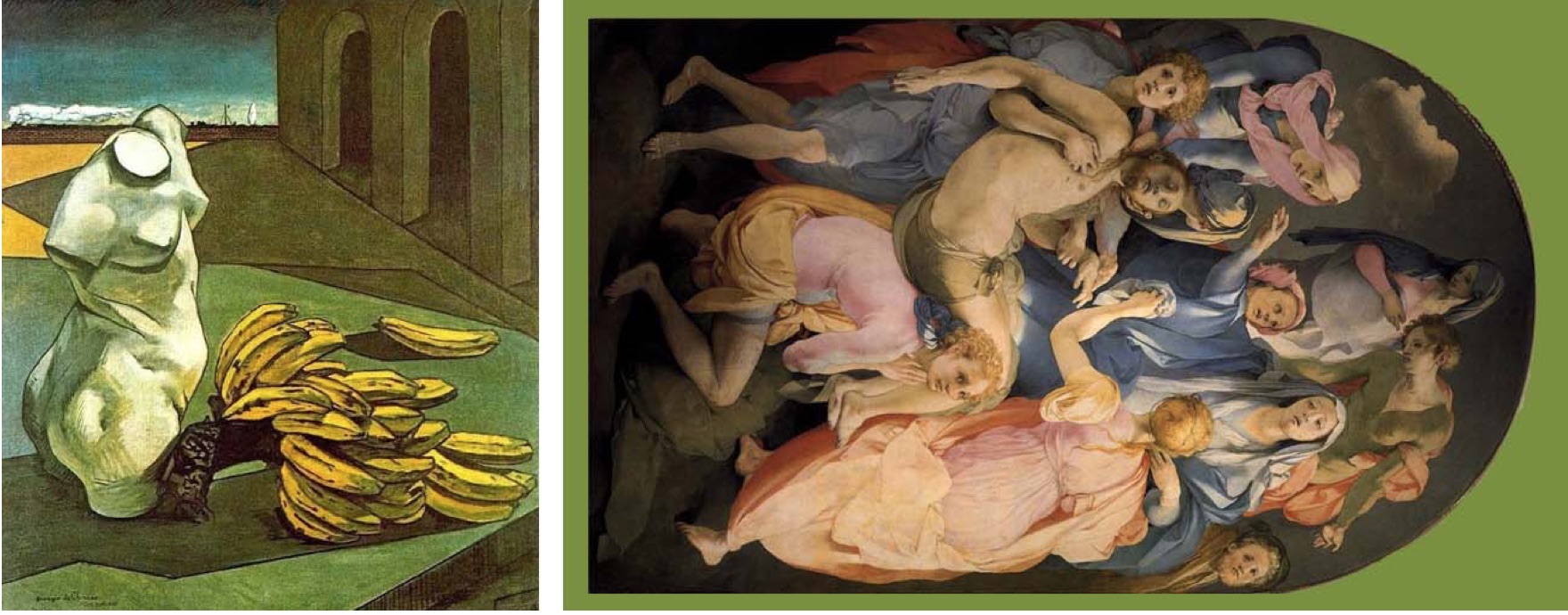

Mine is an effort of collation of arguments produced in the lingua franca by two true artists: each of their own words, carefully chosen by me, can be applied to the green of a Poet’s dream as to the Conical hole of Gordon Matta-Clark or Tiepolo, to the pink of Santa Felicita (or to the Hand that indicates it; who? the Pontormo or Giovanni Anselmo?) as to the black of the Rothko Chapel, to the unbalanced Spiral space of Serra as to the agitation of Erasmus of Narni (who is able to curb it in its stillness?). There are no borders in art, nothing sets and often the classics are revived.

Here is the series of promised quotes. I’ll start with Gould. After pointing out Bach’s indifference if not unwillingness to write for a given keyboard instrument, Gould uses terms such as smug, silken, legato spinning resource for his own Steinway. This says a lot about the attention to the characteristics of one’s own expressive language:

Bach’s compositional method, of course, was distinguished by his disinclination to compose at any specific keyboard instrument. And it is indeed extremely doubtful that his sense of contemporaneity would have appreciably altered had his catalogue of household instruments been supplemented by the very latest of Mr. Steinway’s “accelerated action” claviers. It is at the same time very much to the credit of the modern keyboard instrument that the potential of its sonority—that smug, silken, legato-spinning resource can be curtailed as well as exploited, used as well as abused.

I suspect I may have unwittingly engaged in a dangerous game, ascribing to musical composition attributes which reflect only the analytical approach of the performer. This is an especially vulnerable practice in the music of Bach, which concedes neither tempo nor dynamic intention, and I caution myself to restrain the enthusiasm of an interpretative conviction from identifying itself with the unalterable absolute of the composer’s will. Besides, as Bernard Shaw so aptly remarked, parsing is not the business of criticism.

As for the reasons for his abandonment of concert halls for recording ones:

Well, you see, Bruno, I don’t really enjoy playing any concertos very much. What bothers me most is the competitive, comparative ambience in which the concerto operates. I happen to believe that competition rather than money is the root of all evil, and in the concerto we have a perfect musical analogy of the competitive spirit. Obviously, I’d exclude the concerto grosso from what l’ve just said.

Marliave’s mention of “the intimate and contemplative appeal to the ear“ illustrates an approach to these works based upon philosophical conjecture rather than musical analysis. Beethoven, according to this hypothesis, has spiritually soared beyond the earth’s orbit and, being delivered of earthly dimension, reveals to us a vision of paradisiacal enchantment. A more recent and more alarming view shows Beethoven not as an indomitable spirit which has overleapt the world but as a man bowed and broken by the tyrannous constraint of life on earth, yet meeting all tribulation with a noble resignation to the inevitable. Thus Beethoven, mystic visionary, becomes Beethoven, realist, and these last works are shown as calcified, impersonal constructions of a soul impervious to the desires and torments of existence. The giddy heights to which these absurdities can wing have been realized by several contemporary novelists, notable offenders being Thomas Mann and Aldous Huxley.

If you are particularly fond of the last works of Strauss, as I am, it is essential to acquire a more flexible system of values than that which insists upon telling us that novelty equals progress equals great art. I do not believe that because a man like Richard Strauss was hopelessly old-fashioned in the professional verdict, he was, therefore, necessarily a lesser figure than a man like Schoenberg who stood for most of his life in the forefront of the avant-garde. If one adopts that system of values, it brings about the inevitable embarrassment of having to reject, among others, Johann Sebastian Bach as also being hopelessly old-fashioned.

His opinion on the relationship between the tastes of the time and the eternity of language see the following fragments:

The generation, or rather the generations, that have grown up since the early years of this century have considered the most serious of Strauss’s errors to be his failure to share actively in the technical advances of his time. They hold that having once evolved a uniquely identifiable means of expression, and having expressed himself within it at first with all the joys of high adventure, he had thereafter, from the technical point of view, appeared to remain stationary—simply saying again and again that which in the energetic clays of his youth he had said with so much greater strength and clarity. For these critics it is inconceivable that a man of such gifts would not wish to participate in the expansion of the musical language, that a man who had the good fortune to be writing masterpieces in the days of Brahms and Bruckner and the luck to live beyond Webern into the age of Boulez and Stockhausen should not want to search out his own place in the great adventure of musical evolution. What must one do to convince such folk that art is not technology, that the difference between a Richard Strauss and a Karlheinz Stockhausen is not comparable to the difference between a humble office adding machine and an IBM computer?

The great thing about the music of Richard Strauss is that it presents and substantiates an argument which transcends all the dogmatisms of art—all questions of style and taste and idiom—all the frivolous, effete preoccupations of the chronologist. It presents to us an example of the man who makes richer his own time by not being of it; who speaks for all generations by being of none. It is an ultimate argument of individuality—an argument that man can create his own synthesis of time without being bound by the conformities that time imposes.

But one last examination of this hypothetical piece: let us assume that instead of attributing it to Haydn or to any later composer, the improviser were to insist that it was a long-forgotten and newly discovered work of none other than Antonio Vivaldi, a composer who was by seventy—five years Haydn’s senior. I venture to say that, with that condition in mind, this work would be greeted as one of the true revelations of musical history-a work that would be accepted as proof of the farsightedness of this great master, who managed in this one incredible leap to bridge the years that separate the Italian baroque from the Austrian rococo, and our poor piece would be deemed worthy of the most august programs. In other words, the determination of most of our aesthetic criteria, despite all our proud claims about the integrity of artistic judgment, derives from nothing remotely like an “art-for-art’s-sake” approach. What they really derive from is what we could only call an “art-for-what-its-society-was-once-like” sake.

The deficiencies of this argument arise from the fact that its proponents simply cannot tolerate the idea that the participation in a certain historical movement does not necessarily impose upon the participant the duty to accept the logical consequences of that movement. One of the irresistibly lovable facts about most human beings is that they are very seldom willing to accept the consequences of their own thinking. The fact that Strauss deserts the general movement of German expressionism (presumably, in Rosenfeld‘s terms, the embodiment of “Nietzsche‘s modernism”) should not be more disturbing than the fact that the unquestioned innovator Arnold Schoenberg found it extremely difficult in his later years to fulfill the rhythmic extenuations of his own motivic theories. The fact is that above and beyond the questions of age and endurance, art is not created by rational animals and in the long run is better for not being so created.

It would be most surprising if the techniques of sound preservation, in addition to influencing the way in which music is composed and performed (which is already taking place), do not also determine the manner in which we respond to it. And there is little doubt that the inherent qualities of illusion in the art of recording those features that make it a representation not so much of the known exterior world as of the idealized interior world-will eventually undermine that whole area of prejudice that has concerned itself

with finding chronological justifications for artistic endeavors and which in the post-Renaissance world has so determinedly argued the case of a chronological originality that it has quite lost touch with the larger purposes of creativity.

Whatever else we would predict about the electronic age, all the symptoms suggest a return to some degree of mythic anonymity within the social-artistic structure. Undoubtedly most of what happens in the future will be concerned with what is being done in the future, but it would also be most surprising if many judgments were not retroactively altered because of the new image of art. If that happens, as I think it must, there will be a number of substantial figures of the past and near past who will undergo major reevaluation and for whom the verdict will no longer rest upon the narrow and unimaginative concepts of the social-chronological parallel.

And so it seems to me a great mistake to read into the fantastic transition of music in our time a total social significance. Undeniably, there do exist correlations between the development of a social stratum and the art which grows up around it, just as the public manner of early baroque music related to some degree to the prosperity of a merchant class in the sixteenth century; but it is terribly dangerous to advance a complicated social argument for a change which is fundamentally a procedural one within an artistic discipline.

Of course, the early propagandists for atonality pointed with a good deal of pride to the fact that the movement toward abstract art began at almost exactly the same time as atonality, and there are certain comfortable parallels between the careers of the painter Kandinsky and the composer Schoenberg.

But l think it is dangerous to pursue the parallel too closely, for the simple reason that music is always abstract, that it has no allegorical connotations except in the highest metaphysical sense, and that it does not pretend and has not, with very few exceptions, pretended to be other than a means of expressing the mysteries of communication in a form which is equally mysterious.

The figure of Schoemberg outlined by the writings of G is emblematic for understanding the linguistic work of a great composer and his responsibility in the detachment of cultured music from popular music:

But the odd thing about it was that with this oversimplified, exaggerated system Schoenberg began to compose again; and not only did he begin to compose: he embarked upon a period of about five years which contains some of the most beautiful, colorful, imaginative, fresh, inspired music which he ever wrote. Out of this concoction of childish mathematics and debatable historical perception came an intensity, a ioie de vivre, which knows no parallel in Schoenberg‘s life. How could this be, then? By what strange alchemy was this man compounded that the sources of his inspiration flowed most freely when stemmed and checked by legislation of the most stifling kind? I suppose part of the answer lies in the fact that Schoenberg was always intrigued by numbers and afraid of numbers and attempting to read his destiny in numbers –and, after all, what greater romance of numbers could there be than to govern one’s creative life by them? I suppose part of it was due to the fact that after fifteen years awash in a sea of dissonance, Schoenberg felt himself to be on firm ground once again. Still another part of it is certainly that all music must have a system, and that particularly in those moments of rebirth such as Schoenberg had led us into, it is much more necessary to adhere to the system, to accept totally its consequences, than at a later, more mature stage of its existence.

I think there can be no doubt that its fundamental effect has been to separate audience and composer. One doesn’t like to admit this, but it is true nonetheless. There are many people around who believe that Schoenberg has been responsible for shattering irreparably the compact between audience and composer, of separating their common bond of reference and creating between them a profound antagonism. Such people claim that the language has not become a valid one for the reason that it has no system of emotional reference that is generally accepted by people today. Certainly concert music of today—

that part of it, at any rate, which owes a great deal to the Schoenbergian influence—plays a very small part in the life of many people. It cannot by any means claim to excite the curiosity that was generally aroused by significant new works fifty or sixty years ego. One must remember that at the turn of the century, any new work by a Richard Strauss or a Gustav Mahler or a Rimsky-Korsakov or a Debussy was a major event not only for the cognoscenti but for a very large lay audience as well.

No matter how little interest there may be in the more significant developments of music in our time, I think that there is little doubt that there are some areas in which the vocabulary of atonality—using this term now in a collective sense—has made quite an unobjectionable contribution to contemporary life. It has done this particularly in media in which music furnishes but a part—operas, to a degree (if you can consider styling Alban Berg’s Wozzeck a “hit”), but most particularly in that curious specialty of the twentieth century known as background music for cinema or television. If you really stop to listen to the music accompanying most of the grade-B horror movies that are coming out of Hollywood these days, or perhaps a TV show on space travel for children, you will be absolutely amazed at the amount of integration which the various idioms of atonality have undergone in these media.

Until here: Glenn Gould. Let us now turn to quoting Brodsky. The following fifteen lines (taken from On Grief and Reason) represent an eloquent summary of his thinking on art in general and poetry in particular, as well as on the meaning of the word “language”. Below I have collected other fragments (also taken from Less Than One) that specify its depth and richness. The only fundamental difference with the visual arts is on the affirmation of the inalienability of the word to the semantic value (unfortunately), but with the specification that this does not apply to the other arts.

For poetic discourse is continuous; it also avoids cliché and repetition. The absence of those things is what speeds up and distinguishes art from life, whose chief stylistic device, if one may say so, is precisely cliché and repetition, since it always starts from scratch. It is no wonder that society today, chancing on this continuing poetic discourse, finds itself at a loss, as if hoarding a runaway train. I have remarked elsewhere that poetry is not a form of entertainment, and in a certain sense not even a form of art, but our anthropological, genetic goal, our linguistic, evolutionary beacon. We seem to sense this as children, when we absorb and remember verses in order to master language. As adults, however, we abandon this pursuit, convinced that we have mastered it. Yet what we’ve mastered is but an idiom, good enough perhaps to outfox an enemy, to sell a product, to get laid, to earn a promotion, but certainly not good enough to cure anguish or cause joy. Until one learns to pack one’s sentences with meanings like a van or to discern and love in the beloved’s features a “pilgrim soul”; until one becomes aware that “No memory of having starred I Atones for later disregard, / Or keeps the end from being hard”—until things like that are in one’s bloodstream, one still belongs among the sublinguals. Who are the majority, if that’s a comfort.

In that, it-life-differs from art, whose worst enemy, as you probably know, is cliché. Small wonder, then, that art, too, fail-s to instruct you as to how to handle boredom. There are few novels about this subject; paintings are still fewer; and as for music, it is largely nonsemantic. On the whole, art treats boredom in a self-defensive, satirical fashion. The only way art can become for you a solace from boredom, from the existential equivalent of cliché, is it you yourselves become artists. Given your number, though, this prospect is as unappetizing as it is unlikely.

Herein lies the ultimate distinction between the beloved and the Muse; the latter doesn’t die. The same goes for the Muse and the poet: when he’s gone, she finds herself another mouthpiece in the next generation. To put it another way, she always hangs around a language and doesn’t seem to mind being mistaken for a plain girl. Amused by this sort of error, she tries to correct it by dictating to her charge now

pages of Paradise, now Thomas Hard}-“s poems of 1912-13; that is, those where the voice of human passion yields to that of linguistic necessity—but apparently to no avail. So let’s leave her with a flute and a wreath wildflowers. This way at least she might escape a biographer.

Of course, when talking about the signs of the word (semanticity) one cannot avoid addressing the theme of the relationship between art and life:

Now, the purpose of evolution is the survival neither of the fittest nor of the defeatist. Were it the former, we would have to settle for Arnold Schwarzenegger; were it the latter, which ethically is a more sound proposition, we’d have to make do with Woody Allen. The purpose of evolution, believe it or not, is beauty, which survives it all and generates truth simply by being a Fusion of the mental and the sensual. As it is always in the eye of the beholder, it can’t he wholly embodied save in words: that’s what ushers in a poem, which is as incurably semantic as it is incurably euphonic.

In “Home Burial“ (Frost’s poem) it results is both. For every Galatea is ultimately a Pygmalion’s self-projection. On the other hand, art doesn’t imitate life but infects it. …

… This is a poem about languages terrifying success, for language, in the final analysis, is alien to the sentiments it articulates. No one is more aware of that than a poet; and if “Home Burial”

is autobiographical, it is so in the first place by revealing Frost’s grasp of the collision between his métier and his emotions. To drive this point home, may I suggest that you compare the actual sentiment you may feel toward an individual in your company and the word “love.” A poet is doomed to resort to words. So is the speaker in “Home Burial.” Hence, their overlapping in this poem; hence, too, its autobiographical reputation. …

… So what was it that he was after in this, his very own poem? He was, I think, after grief and reason, which, while poison to each other, are languages most efficient fuel—or, if you will, poetry’s indelible ink. Frost’s reliance on them here and elsewhere almost gives you the sense that his dipping into this ink pot had to do with the hope of reducing the level of its contents; you detect a sort of vested interest on his part. Yet the more one dips into it, the more it brims with this black essence of existence, and the more one’s mind, like one’s fingers, gets soiled by this liquid. For the more there is of grief, the more there is of reason. As much as one may be tempted to take sides in “Home Burial,” the presence of the narrator here rules this out, for while the characters stand, respectively, for reason and for grief, the narrator stands for their fusion. To put it differently, while the characters’ actual union disintegrates, the story, as it were, marries grief to reason, since the bond of the narrative here supersedes the individual dynamics— well, at least for the reader. Perhaps for the author as well. The poem, in other words, plays fate.

For poetic discourse is continuous; it also avoids cliché and repetition. The absence of those things is what speeds up and distinguishes art from life, whose chief stylistic device, if one may say so, is precisely cliché and repetition, since it always starts from scratch. It is no wonder that society today, chancing on this continuing poetic discourse, finds itself at a loss, as if hoarding a runaway train. I have remarked else-

where that poetry is not a form of entertainment, and in a certain sense not even a form of art, but our anthropological, genetic goal, our linguistic, evolutionary beacon. We seem to sense this as children, when we absorb and remember

For art is something more ancient and universal than any faith with which it enters into matrimony, begets children—but with which it does not die. The judgment of art is a judgment more demanding than the Final Judgment.

Rilke’s Orfeo gives him the cue to clarify his thought on art, which in addition to the close relationship with the meaning of death, arises precisely from the rubbish of life:

This economy is art’s ultimate raison d’être, and all its history is the history of its means of compression and condensation. In poetry, it is language, itself a highly condensed version of reality. In short, a poem generates rather than reflects.

For why should we empathize with him? Less highborn and less gifted than he is. we never will be exempt from the law of nature. With us, the journey to Hades is a one-way trip. What can we possibly learn from his story? That a lyre takes one farther than a plow or a hammer and anvil? That we should emulate geniuses and heroes? That perhaps audacity is what does it? For what if not sheer audacity was it that made him undertake this pilgrimage?

A man of my occupation seldom claims a systematic mode of thinking; at worst, he claims to have a system—but even that, in his case, is a borrowing from a milieu, from a social order, or from the pursuit of philosophy at a tender age. Nothing convinces an artist more of the arbitrariness of the means to which he resorts to attain a goal—however permanent it may be—than the creative process itself, the process of composition. Verse really does, in Akhmatova’s words, grow from rubbish; the roots of prose are no more honorable. …

… Art, generally speaking, always comes into being as a result of an action directed outward, sideways, toward the attainment (comprehension) of an object having no immediate relationship to art. It is a means of conveyance, a landscape flashing in a window—rather than the conveyance’s destination. “If you only knew,” said Akhmatova, “what rubbish verse grows from . . .” The farther away the purpose of movement, the more probable the art; and, theoretically, death (anyone’s, and a great poet’s in particular, for what can be more removed from everyday reality than a great poet or great poetry?) turns into a sort of guarantee of art.

The hierarchy between ethics and aesthetics further clarifies his thinking on the relationship between art and life. This applies to all the arts, as the discourse about what art language means also always applies to all:

On the whole, every new aesthetic reality makes man’s ethical reality more precise. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics. The categories of “good” and “bad” are, first and foremost, aesthetic ones, at least etymologically preceding the categories of “good” and “evil.” If in ethics not “all is permitted,” it is precisely because not “all is permitted” in aesthetics, because the number of colors in the spectrum is limited. The tender babe who cries and rejects the stranger who, on the contrary, reaches out to him, does so instinctively, makes an aesthetic choice, not a moral one.

Unlike life, a work of art never gets taken for granted: it is always viewed against its precursors and predecessors. The ghosts of the great are especially visible in poetry, since their words are less mutable than the concepts they represent.

In such an absence, art grows humble. For all our cerebral progress, we are still greatly subject to relapse into the Romantic (and, hence, Realistic as well) notion that “art imitates life.” If art does anything of this kind, it undertakes to reflect those few elements of existence which transcend “life,” extend it beyond its terminal point—an undertaking which is frequently mistaken for art’s or the artist’s own groping for immortality. In other words, art “imitates” death rather than life; i.e., it imitates that realm of which life supplies no notion: realizing its own brevity, art tries to domesticate the longest possible version of time. After all, what distinguishes art from life is the ability of the former to produce a higher degree of lyricism than is possible within any human interplay. Hence poetry’s affinity with–if not the very invention of—the notion of afterlife.

Poetry after all in itself is a translation; or, to put it another way, poetry is one of the aspects of the psyche rendered in language. It is not so much that poetry is a form of art as that art is a form to which poetry often resorts. Essentially, poetry is the articulation of perception, the translation of that perception into the heritage of language—language is, after all, the best available tool. But for all the value of this tool in ramifying and deepening perceptions-revealing sometimes more than was originally intended, which, in the happiest cases, merges with the perceptions—every more or less experienced poet knows how much is left out or has suffered because of it.

It would be false as well as unnecessary to try to divorce Platonov from his epoch; the language was to do this anyway, if only because epochs are finite. In a sense, one can see this writer as an embodiment of language temporarily occupying a piece of time and reporting from within. The essence of his message is LANGUAGE I5 A MILLENARIAN DEVICE, HISTORY ISN’T”, and coming from him that would be appropriate.

A great writer is one who elongates the perspective of human sensibility, who shows a man at the end of his wits an opening, a pattern to follow.

Burning books, after all, is just a gesture; not publishing them is a falsification of time. But then again, that is precisely the goal of the system: to issue its own version of the future.

Whether one likes it or not, art is a linear process. To prevent itself from recoiling, art has the concept of cliché. Art’s history is that of addition and refinement, of extending the perspective of human sensibility, of enriching, or more often condensing, the means of expression. Every new psychological or aesthetic reality introduced in art becomes instantly old for its next practitioner. An author disregarding this rule, somewhat differently phrased by Hegel, automatically destines his work—no matter what good press it

gets in the marketplace—-to assume the status of pulp.

But to clarify the undemocratic nature of the language, just these sketches taken from some of his most important essays are enough:

Herein, of course, lies arts saving grace. Not being lucrative, it falls victim to demography rather reluctantly.

For if, as we’ve said, repetition is boredom’s mother, demography (which is to play in your lives a far greater role than any discipline you’ve mastered here) is its other parent. This may sound misanthropic to you, but I am more than twice your age, and I have lived to see the population of our globe double. By the time you’re my age, it will have quadrupled, and not exactly in the fashion you expect. For instance, by the year 2000 there is going to be such cultural and ethnic rearrangement as to challenge your notion of your own humanity.

Starting with the authors mentioned above, some may find these notes maximalist and biased; most likely they will ascribe these flaws to their author’s own métier. Still others may find the view of things expressed here too schematic to be true. True: it’s schematic, narrow, superficial. At best, it will be called subjective or elitist. That would be fair enough except that we should bear in mind that art is not a democratic enterprise, even the art of prose, which has an air about it of everybody being able to master it as well as to judge it.

For poetic discourse is continuous; it also avoids cliché and repetition. The absence of those things is what speeds up and distinguishes art from life, whose chief stylistic device, if one may say so, is precisely cliché and repetition, since it always starts from scratch. It is no wonder that society today, chancing on this continuing poetic discourse, finds itself at a loss, as if hoarding a runaway train. I have remarked elsewhere that poetry is not a form of entertainment, and in a certain sense not even a form of art, but our anthropological, genetic goal, our linguistic, evolutionary beacon. We seem to sense this as children, when we absorb and remember

The evaluation of reality made through such a prism—the acquisition of which is one goal of the species—is therefore the most accurate, perhaps even the most just. (Cries of “Unfair!” and “Elitistl” that may follow the aforesaid from, of all places, the local campuses must be left unheeded, for culture is “elitist” by definition, and the application of democratic principles in the sphere of knowledge leads to

equating wisdom with idiocy.)

taking inspiration from a poem by W. Auden, B. engraves his thoughts on language:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet.

But for once the dictionary didn’t overrule me. Auden had indeed said that time (not the time) worships language, and the train of thought that statement set in motion in me is still trundling to this day. For “worship” is an attitude of the lesser toward the greater. If time worships language, it means that language is greater, or older, than time, which is, in its turn, older and greater than space. That was how I was taught, and I indeed felt that way. So if time—which is synonymous with, nay, even absorbs deity—worships language, where then does language come from? For the gift is always smaller than the giver. And then isn’t language a repository of time? And isn’t this why time worships it?

Uncertainty, you see, is the mother of beauty, one of whose definitions is that it’s something which isn’t yours. At least, this is one of the most frequent sensations accompanying beauty. Therefore, when uncertainty is evoked, then you sense beauty’s proximity. Uncertainty is simply a more alert state than certitude, and thus it creates a better lyrical climate. Because beauty is something obtained always from without, not from within. And this is precisely what’s going on in this stanza.

But you don’t dissect a bird to find the origins of its song: what should be dissected is your ear. In either case, however, you’ll be dodging the alternative of “We must love one another or die,” and I don’t think you can afford to.

Già pubblicato in italiano su Fyinpaper il 25 febbraio 2021.

Already published in italian on Fyinpaper on February 25, 2021