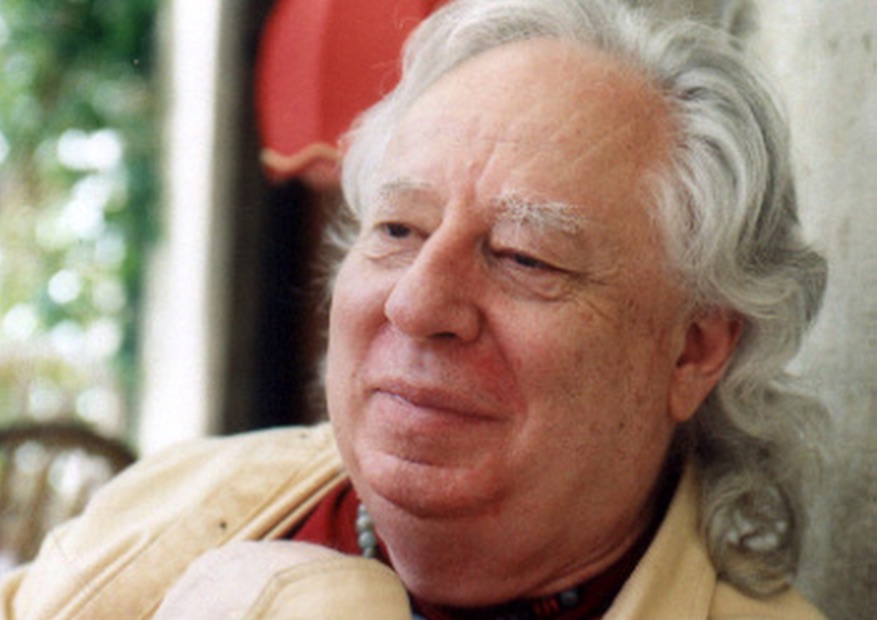

You are a leading internationally known figure in the field of arts, but also a well recognized artist-photographer and poet. Two years ago, you celebrated your birthday (84) publishing another collection of your poems titled “Surviving”. What did you intend refer to?

“First of all, simply to the fact of having been alive for so long. I will be 87 at the end of February. Secondly, to the fact that I am still very active in the world of the arts, not brooding in some retirement home.”

In one of the various interviews you released, you told about your activism in the poetry field as a runner, in London, precisely in the decades Fifties and Sixties. Can you remind us what was the social and cultural climate in that city at that time? In your opinion, what would be relationship to today’s cultural climate in London?

“By “runner” what you mean is that I was the chair-person and organizer of a group of poets (just called The Group) who met at my flat in London every week. Texts of the poems to be discussed were distributed in advance, and just one poet read on each occasion. It wasn’t a free for all. I didn’t found the group – I inherited it from Philip Hobsbaum, when he moved to Belfast and founded another group in that city. Seamus Heaney, the Irish poet who became a Nobel Prizewinner for literature, was a member of this Belfast group. The two groups used to exchange what we called ‘song-sheets’. The poetry world was much smaller then than it is now. Performance poetry, related to rap, was less important. There was a smaller range of ethnicities.”

You had the opportunity to stress your admiration for two important public figures who were also poets, Sir Thomas Wyatt (XVI century) and John Wilmot, the Earl of Rochester (XVII century). All this happens in spite of the deep difference, in style and tune, with your poems. What are the main features of the two personalities which particularly touched you?

“Basically, that they were both completely independent and not literary careerists. Poetry was part of their lives, but certainly not all of their lives. I never wanted to be a ‘professional poet’. It creates too many burdensome expectations if that’s how people see you.”

Your life is very rich as far as its geographical background is concerned. I ask you if, and in case how, this richness of yours affected your poems as well as your critical and theoretical writing, alongside with your growth as an international intellectual.

“Basically, I’m a child of the British Empire, rather than specifically British. My father’s family have lived in the Caribbean region – Barbados, then Demerara (now Guyana), then Jamaica, from around 1630. My mother was descended from an 18th century chairman of the British East India Company. My father and my mother met because of World War I. He was already established as a civil servant in Jamaica, but came to Europe to fight after his younger brother, who belonged to the West India Regiment, was killed. He was gassed early in 1918, and – now considered as unfit to fight at the front – was send across the Channel to be the ADC of an elderly home-front general, who was my mother’s uncle. My dad returned to Jamaica to be demobilized in September 1919 – that is a whole year after the war ended. He promptly made a mixed-race son, whom I learned about only fairly recently. This son was given my father’s unusual fore-name – Dudley – and used our even-more unusual surname, Lucie-Smith. He has descendants in Jamaica who are convinced that my dad and their grandmother were married, but I don’t think that is true. Realizing that he couldn’t, at that period, stay in the British civil service with a mixed-race wife, he returned to Britain on leave in the summer of 1922 and proposed to my mother, who was an orphan. In the spring of 1923she came out to Jamaica and married him. I appeared in 1933, ten years after the marriage. My father died of lung cancer in 1943 – he was a heavy smoker but having been gassed can’t have helped. My mother got out of Jamaica in 1946 and brought me to post-World War II Britain to be educated. I won a scholarship for the sons of civil servants at King’s School Canterbury, then, after that, a full scholarship at Merton College Oxford.

My suspicion now is that my dad remained in touch with his alternative family – I saw very little of him when I was a child, but that, in any case, was typical of old-style colonial society.

Both sides of my family were slave-owners in the West Indies in the 18th and early 19th centuries. However my great-grandfather on my mother’s side was a Member of Parliament who was closely allied to Wilberforce in fighting the slave-trade, so tale your pick.

I had my DNA analyzed a few years back. I have no African blood. I am 18 percent Jewish – a great-grandmother on my father’s side who belonged to a Jewish family who emigrated in the early 19th century from Venezuela to Curacao. One of them was a sea-captain – a very unexpected thing for a Jew to be. I am slightly less that 50 per cent European Caucasian. The rest is Finnish, or possibly Estonian. I have no information about that. Finns are basically Central Asian immigrants who moved, in the very long ago, to the shores of the Baltic. All this mixed blood comes from my father’s side, as far as I can make out. The West Indies were a melting pot.

In Britain my father’s European ancestors were categorized as ‘London Dutch’, but ‘Lucie’, which they started to use in the mid-18th century, is emphatically not a Dutch name. My guess is that it is originally Huguenot French. Apologies for the length of this, but it explains how, under the umbrella of the British Raj, I come both from everywhere and from nowhere.

Perhaps this is why I’ve travelled so much – maybe more than poets – and indeed others – who are classified as travelers. If a country has something that can be called an art world, it’s 80% certain that I’ve been there. Some omissions I regret. For example, I’ve never been to Poland. Nor to Pakistan. But to China, Russia, Japan, Iran, most of Europe, most of Latin America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand. Much of the United States. Yes.”

You normally compose your poems in a private and intimate atmosphere. But when you deal with social or public subjects, you do this in a very synthetic and strong way. One can find an example even in your already mentioned “Surviving” collection. I particularly refer to “Preaching to the converted”. It looks like a kind of secular decalogue for individual behaviour in society. Vibrant and very dry and harsh is your message about “What you want to hear” and about “What you don’t want news of”. For instance, “war is bad”. But, by the way: what’s your vision about this matter, considering the current geopolitical phenomena worldwide?Regarding global warming, have you any idea to solve the problem, or, at least, to dominate it? The list is short but bears fundamental matters, such as the closing sentence: “What you don’t what to hear is this poem”. Do you think that in our era, which dislikes poetry, the latter can help us?

“I try to look at the world as it is, not as I might want it to be, In Victorian times, my mother’s family were what was then called ‘logical positivists’, which means that they were, in today’s terms, atheists. The paradox is that one of them, my great-uncle Vernon Lushington, was responsible for introducing Burne-Jones to Rossetti, thus setting in motion the second phase of the Pre-Raphaelite Movement. Which was very different from its first phase and led on to European Symbolism and Blue Period Picasso.

I wouldn’t presume to tell people how to put a stop to global warming. If they don’t take steps humanity itself maybe will be wiped out. But, being so old, I won’t be here to see that. And I don’t think I’ll be sitting upstairs on a cloud, saying “I told you so.” Should I find myself on that cloud, looking down at events, I’m more likely to say: “Tout passe, tout lasse, tout casse” – there are millions of other planets, can I please look at a nicer one?

The reader is likely to feel as if your “Surviving” collection has been performed together with Joe Machine, a very impressive artist who has illustrated the book. How did you plan this deep pattern of collaboration?

“It’s an odd alliance. I like Joe very much as person. I also like his work as a painter. We just happened to get together He’s very different from me – sturdily working-class, got dome of his early education in Borstal (juvenile prison). His work shows that there is a future for narrative art, pictorial stories of a kind that anyone, whatever language they speak, can hope to absorb. Figurative art talks to a wider public than poetry. And it’s more specific than music. It’s not the only thing that art can do, but it’s an important part of what it does. If you look at the history of Russian art in the past century or so, figurative art was always there, and never entirely stopped being experimental. Russian abstraction (Futurism) came to a complete halt around 1923, except among Russian artists who emigrated, and had to start again with perestroika in the 1980s.

Here is the West, Minimal Abstraction, a big deal in the 1970s, now looks pretty much dead and the more recent abstract revival that took place in the middle 2000s, was pretty much wiped out by the financial crash of 2007. What seem to matter now are social issues, and also collaborations between art and technology – immersive art, if you like. The Video Games universe is currently a lot more advanced in this respect than the whole flock of current artists who make dinky little ‘art’ videos you can play on your iPhone.

Between your photography and your poetry where your deepest soul is more properly expressed? And which of them does make you happier?

I don’t really distinguish between the two. Photography is a way of seeing the world and showing other people what you see. Poetry is a way of talking about the world in a way that you hope other people will understand.”