Art and Quarantine

1.

Fantastic stories sometimes anticipate the future, even when their “visions” seem madness in their time. These prophetic “appearances” ignite the Fantastico of artists, writers, directors, through their narratives.

The many today’s fantastic imaginaries (like those of the past) are the subject of a debate, held in Fiuggi (2018). Here, the proposals regarding the magazines Antares (Ed. Bietti), Cosmic Dimension and Diònysos (Ed. Tabula fati) were presented with contributions by Gianfranco de Turris, Max Gobbo and mine.

The philosopher Giovanni Sessa “re-reads”, for the aforementioned event, imaginaries that cross times: “In full Baroque, Giambattista Basile had a hint with his Lo cunto de li cunti. In his forty-nine short stories, alterations of the random chain follow one another, which make it possible for the ‘upside down world’ to unfold. It has the traits of a deforming mirror (…), much more than any account of real facts. The fairy tale and the fantastic story are mostly ‘true’ in inverse proportion to their plausibility. The Fantastico elucidates the feeble distance that distinguishes experience from fantasy, saying that what is known always contains the unknown. (…) In the seventeenth century, during the golden age literature, Don Quixote gave himself back what Bruno knew: it is the ‘individual’ nature that shows the divine seal “.

2.

The body-machine is an intriguing journey through time: like the one whcih starts from futurist robots to get to today’s cyborg.

“We are about to witness the birth of the Centaur and soon we will see the first Angels fly,” writes Marinetti, who has been developing theories of mechanical art and who has been imaging the man-machine since the beginning of Futurism. The multiplied man “whom we dream of, will not know the tragedy of old age (…) we aspire to the creation of a non-human and mechanical type of man, built for an omnipresent speed (…). We believe in the possibility of an incalculable number of human transformations, and without smiling we declare that wings sleep in man’s flesh “(The multiplied Man and the Kingdom of the Machine, 1910).

In the novel Mafarka the futurist (1909), Marinetti imagines an African king who succeeds in the undertaking of building a mechanical son by himself, the result of pure will. These ideas connect Futurist thinking with Nietzsche’s philosophy: to create an entity capable of going beyond man. In 1920, Marinetti became a libertine and libertarian author with the text Sexual electricity, in which a man and a woman split into two electric robots.

In 1921 André Deed made the film The mechanical man, with which he created one of the first representations of cinema on the theme of robot as science fiction, taking up the ideas expressed by Marinetti.

In Futurism, the body-machine has a visual representation in mechanical ballets. Its human and mechanical parts become complementary and opposite together: it is the puppet and the superman. The vision of its movement is expressed by some artists: as in the paintings of Gino Severini on the theme of Tango (1913), in the plastic puppets of Fortunato Depero.

3.

Futurism, with its challenge to the stars, enters the current fantastic narrative with multiple expressions. In recent years there have been numerous publications on the subject.

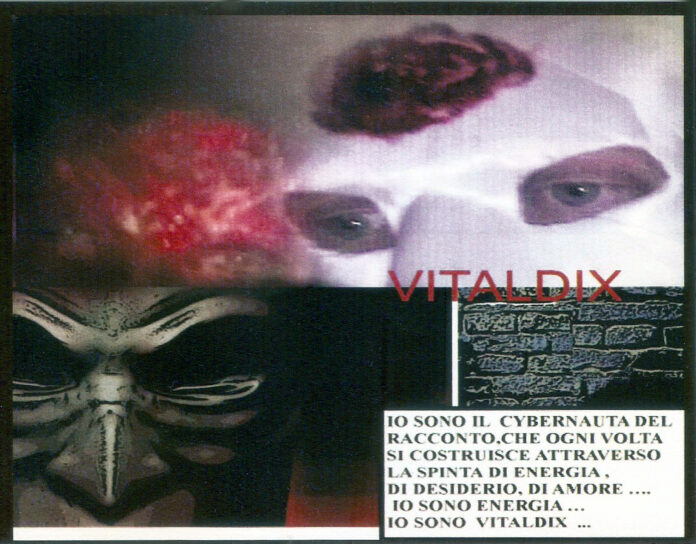

An issue of the IF magazine is dedicated to Futurismo come Fantastico (Ed. Odoya, n. 21, 2017), on c. by Alessandro Scarsella. Here, I present a story on the birth of Vitaldix, my avatar of fantastic-virtual narration, through a flight-poem (2009) with which I celebrated the centenary of Futurism.