Paris in literature

Paris became a myth in French and in foreign literature as early as the 18th century. An example of Paris in literature: Restif de la Bretonne in the Nuits de Paris. In the following century the apex is reached. Émile Zola dedicates to the city a book simply called Paris where he praises its boulevards, its hectic life, its shops, its monuments and its inhabitants which reveal a trembling modernity.

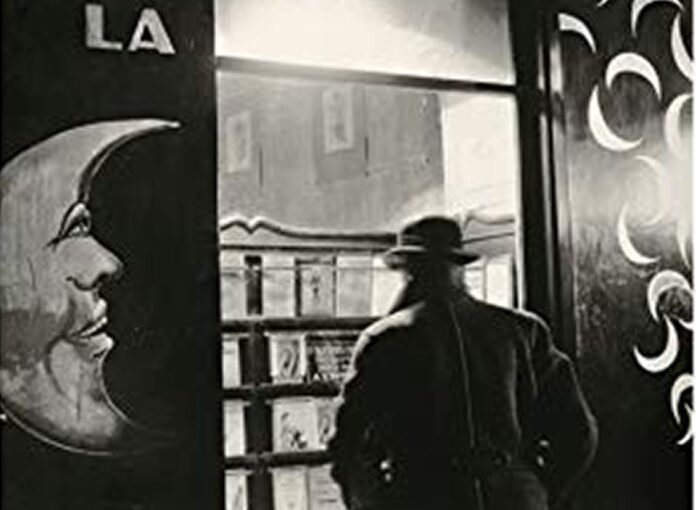

Many authors have devoted themselves exclusively to its history, or to the pleasure of walking its streets, such as Léon-Paul Fargue. Later, the surrealists imagined walks which were moved by chance, highlighting the magic of the new city life: Le Paysan de Paris de Louis Aragon, Nadja by André Breton, Les Dernières nuits de Paris de Philippe Soupault. And no one can forget the crazy runs along the Parisian street that Louis-Ferdinand Céline describes with a kind of futurist fury in his brilliant novel Mort à crédit.

Parisian address books

Numerous books have been written about the places where great artists or great writers lived in the capital French. But no one has ever had the idea to write a book where the Parisian addresses of the characters of memorable novels set in the Ville-Lumière are carefully indicated.

Didier Blonde has signed a very funny (and very interesting) Carnet d’adresses (L’Arbalète Gallimard, 254 pages, 2010). He had to do several researches and consult the old Didot-Bottin at the Bibliothèque Nationale to find these fictional addresses. This project probably started when he noticed that Arsène Lupin, the famous gentleman-cambrioleur created by Maurice Leblanc, was supposed to live incognito in the same street where he lives in Neuilly, at 95 rue Charles-Laffite. Of course, it is not uncommon that these places do not correspond to the descriptions made by the authors. But they do exist.

Human and urban plots

Let’s consider the colossal work of Honoré de Balzac, La Comédie humaine, which he downsized, but he was never able to finish because he died at fifty. This man wanted to describe the totality of society of his time and was always meticulous in his geography. For example, when he talks about his hero Lucien Chardon de Rubempré, who appears in Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes (1837-1843), he makes him stay first in a hotel located in the rue de l’Echelle (now rue Cambon), then in a more miserable hotel in rue de Cluny (now rue Victor-Cousin). He often goes to rue Vendéme where his mistress is staying, then moves to rue Cassette, not far from the church of Saint-Sulpice. Later, he chooses a more elegant residence in quai Malaquais to be closer to another of his mistresses, Esther. Finally, we find him in the prison of the rue Payenne (now rue Malher).

This precision makes the parable of this man more credible. He comes from Angouleme, establishes himself in society and ends up in the cemetery of the Père-Lachaise. In Stendhal’s case, a similar attitude occurs. Lucien Leuwen, in the book of the same name (started in 1834 and never finished but published anyway in 1844) lives at number 43 of rue de Londres, in the new district named Europe. Paris changed a lot at the beginning of the nineteenth century and the new neighborhoods are immediately used by writers. In the Misérables (1862), Victor Hugo first thought of giving a refuge to Jean Valjean at number 50-52 of the boulevard de l’Hôpital, then hid him in the convent of petit-rue Picpus, (now rue Picpus). Later, as a rich and powerful man, Stendhal makes him stay in rue Plumet, where he can also enjoy a beautiful garden (he also owns an apartment in rue de l’Homme-Armé).

Modern geographies of literature

With delight we go back in time to get to the present day. Among all the authors who used Paris to build their own plots, it is useful to quote Patrick Modiano. Almost all his novels are an exploration of various parts of the capital, often of places without great historicalor other interest. For example, in Une jeunesse (1981), his characters are in streets of little importance such as the rue Langeac, where Louis lives. Odile lives in an attic beyond the Champerret Porte and then, when she marries Louis, returns with him to a studio atnumber 18 of the sad rue Caulaincourt, behind Montmartre.

Didier Blonde offers us a new way to read trans-Alpine literature and to visit Paris – a Paris that really exists (or existed), but that only makes sense in the minds of writers.